An early look at HNSW performance with pgvector

(Disclosure: I have been contributing to pgvector, though I did not work on the HNSW implementation outside of testing).

The surge of usage of AI/ML systems, particularly around generative AI, has also lead to a surge in requirements to store its output, vector data, in databases. For more details on this, please read my previous post on how vectors are the new JSON, as they are the lingua franca in AI/ML systems.

pgvector is an open source extension that lets you store vector data in PostgreSQL and perform nearest neighbor (K-NN) searches to find similar results. This includes support for exact nearest neighbor searches via scanning an entire table, and “approximate nearest neighbor” (ANN) via indexing. ANN indexes let you perform faster searches over your vector data, but with a tradeoff of recall", where “recall” is the percentage of relevant results returned. A typically K-NN query looks something like this:

SELECT * FROM table ORDER BY embedding <-> query_vector LIMIT 10;

Prior to the v0.5.0 release, pgvector supported one indexing method: ivfflat. To build an index, the ivfflat algorithm samples (looks over a subset) your vector data, uses a k-means algorithms to define a number of lists (or “centers”), and indexes the vectors in the table by assigning each of them to its closest “list” by distance (e.g. L2 distance, cosine distance). When querying your vector data, you can select how many lists to check using the ivfflat.probes config parameter. Setting a higher value of ivfflat.probes increases recall but can decrease query performance.

The ivfflat method has many advantages, including its simplicity to use, speed in building the index, and ability to use it as a “coarse quantizer” when indexing over large datasets. However, other algorithms, including “hierarchical navigable small worlds” HNSW, provide other methodologies for improving the performance / recall ratio of similarity searches. Many HNSW implementations have demonstrated favorable performance/recall tradeoffs, but usually this comes at a cost of index building time.

Starting with v0.5.0, pgvector has support for hnsw thanks to Andrew Kane. Much like its ivfflat implementation, pgvector users can perform all the expected data modification operations with an hnsw including insert/update/delete (yes – hnsw in pgvector supports update and delete!). The HNSW algorithm is designed for adding data iteratively and does not require to index an existing data set to achieve better recall. For more information on how HNSW works, please read the original research paper.

While v0.5.0 is not out at the time of this blog post, I wanted to provide an early look at HNSW in pgvector given the excitement for this feature. The rest of this blog post covers how I ran the experiment and some analysis.

Testing performance / recall of the pgvector HNSW implementation

When testing ANN indexing algorithms, you cannot look only at query performance. You may have an indexing algorithm that returns results quickly, but if the recall of those results is low, you may not be delivering the best possible results to your users. This is why it’s important to measure recall alongside performance to understand how you can optimize your index for both speed and relevance of your search results.

It’s also important to see how long it takes to build an index. This is a practical consideration for running vector storage systems in production, as different implementations may need to take locks on the primary table that prevent changes during a build. PostgreSQL offers the ability to both create indexes concurrently and to reindex concurrently, which lets you continue to make changes to data in a table without blocking writes.

Here’s a summary of different performance attributes that I analyzed in this experiment:

- Performance / Recall ratio: As mentioned, in ANN indexes, you must look at both performance AND recall to make an informed judgement on how well the index worked.

- Index build time: How long does it take to build the index? This affects both maintaining the index and how quickly you can add additional data.

- Index size: How much space does the index take up on disk? (This lead to a small patch in the ANN Benchmark suite, and a major kudos to their quick review!)

For this experiment, I focused entirely on optimizing my environment for performance, particularly around keeping the workload in memory. I used an r7gd.16xlarge (64 vCPU, 512GM RAM) instance with my PostgreSQL data directory installed directly on the local NVMe. I used PostgreSQL 15.3 and ran all of the tests locally, i.e. the benchmarking suite connected directly to the PostgreSQL instance over a local socket. I used the ANN Benchmark test framework (more on this below), ran one test at a time, and note that the framework runs a single query at a time.

For test data, I used the following known data sets from the ANN Benchmark suite. In the parenthesis, I use (data set size, vector dimensions):

- mnist-784-euclidean (60K, 784-dim)

- sift-128-euclidean (1M, 128-dim)

- gist-960-euclidean (1M, 960-dim)

- dbpedia-openai-1000k-angular (1M, 1536-dim)

Running these with the ANN Benchmark testing suite required creating new modules for the HNSW implementation for pgvector where I did the following:

- Store the vectors in the table using

PLAINstorage, i.e. the data was not TOASTed but stored inline. - Built the index (and measured total build time + index size)

- Prewarmed the shared buffer cache to start with the table and index data in memory.

For PostgreSQL configuration, I had the following settings, with a focus on keeping the workload in memory:

shared_buffers: 128GBeffective_cache_size: 256GBwork_mem: 4GBmaintenance_work_mem: 64GBmax_wal_size: 20GBwal_compression: zstdcheckpoint_timeout: 2hjit: off

Additionally, as parallelism in the index building process for ivfflat is also a pgvector v0.5.0, I’ll note the following parallelism settings:

max_worker_processes: 128max_parallel_workers: 64max_parallel_maintenance_workers: 64max_parallel_workers_per_gather: 64min_parallel_table_scan_size: 1

Next, we need to consider what parameters we need to test and vary for testing the HNSW implementation. hnswlib as an explanation for how the different parameters work, with my attempt to summarize them below:

M: An index building parameter that indicates how many bidirectional links (or paths) exist between each indexed element. This is a key piece in how we search over an HNSW index.ef_construction: An index building parameter that indicates how many nearest neighbors to check while adding an element to the index.ef_search: This is a search parameter that indicates the number of nearest neighbors to keep in a “dynamic list” while keeping the search. A large value can improve recall, usually with a tradeoff in performance. You needef_searchbe at least as big as yourLIMITvalue.

To set up the actual code to test, given this is a moving target, I picked pgvector at commit 600ca5a7 to test both its ivfflat and HNSW implementation. To have an additional implementation to compare against, I also selected pg_embedding, another recent HNSW implementation targeted for PostgreSQL. In summary, I tested each implementation at the following commits, which we the latest when I ran these tests:

Finally, we need test parameters. For ivfflat, I used the existing configuration in ANN Benchmark that varies lists and probes. For the HNSW algorithms, I took the test parameters from the mirrored test parameters from the other HNSW implementations, but only test a subset of construction parameters.

- Construction

- M=12, ef_construction=60

- M=16, ef_construction=40

- M=24, ef_construction=40

- Search: ef_search=10, ef_search=20, ef_search=40, ef_search=80, ef_search=120, ef_search=200, ef_search=400, ef_search=600, ef_search=800,

(I do want to personally understand the impact of the construction parameters more, and will be running tests in the future that dive further into the variations. However, running the test suite does take time!)

Running these with the ANN Benchmark suite required creating new modules. Credit to Pavel Borisov for most of the work on the pg_embedding HNSW test. I anticipate portions of this work to be proposed for the upstream ANN Benchmark project once HNSW is released for pgvector.

So, how did the tests go?

Results and Analysis

The first thing to emphasize is that these tests were conducted at a specific point in time in all the projects involved. The results today may not match the results tomorrow, but they provide a directional snapshot of where things stand today. I also wanted to use this as an exercise to highlight the tradeoffs on where you may want to use ivfflat vs. hnsw, as both indexes have utility.

For the rest of this section, we’ll look at the tests in each data set, and explore:

- The query performance / recall ratio

- Index build time

- Index size

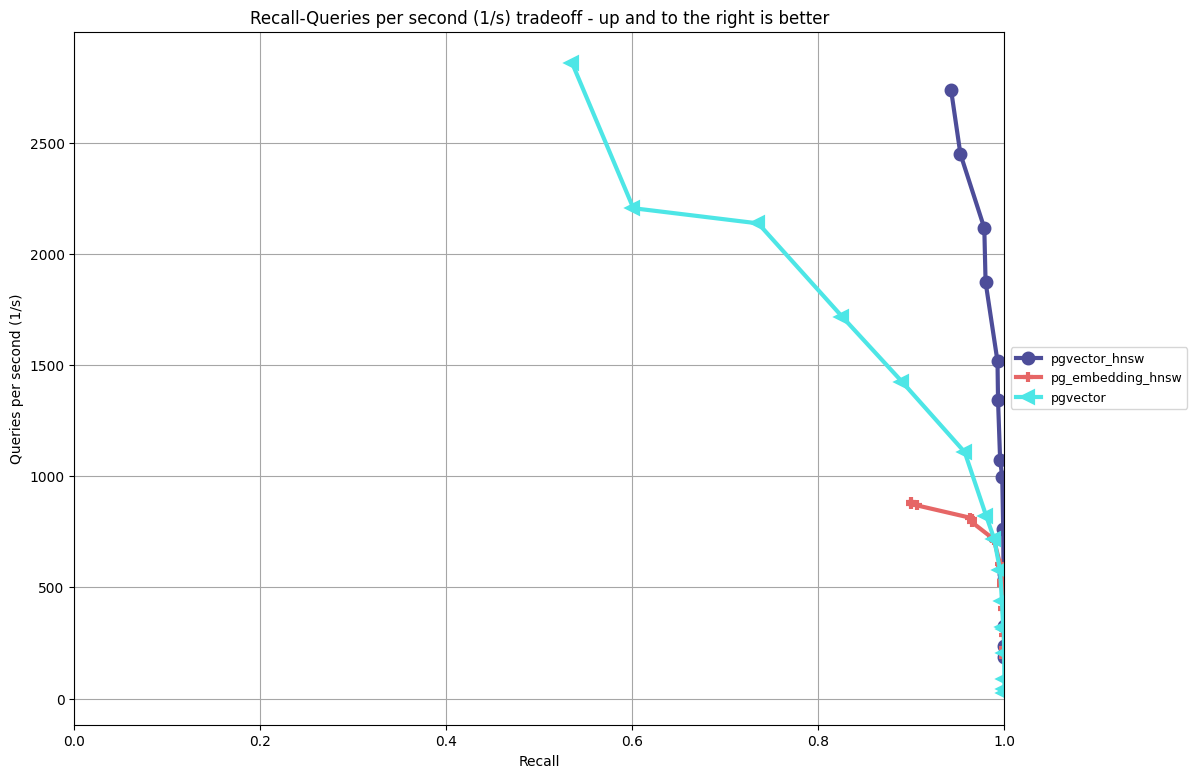

mnist-784-euclidean (60K, 784-dim)

This is my “sanity check” data set: it’s not too large (you can run tests quickly), but it also has higher dimensionality vector (you can see some of the oddities that come with higher dimensions). I have used it to successfully hunt down obvious performance regressions.

pgvector (ivfflat)

| Parameters | Build time (min) |

|---|---|

| lists=100 | 0.19 |

| lists=200 | 0.20 |

| lists=400 | 0.24 |

| lists=1000 | 0.54 |

| lists=2000 | 0.91 |

| lists=4000 | 1.56 |

NOTE: I did not get the index size as I did not run the test with this patch in place. However, the index size is roughly the same size as the vector column indexed in the table, plus overhead with the lists

pgvector_hnsw (hnsw)

| Parameters | Build time (min) | Index size (MB) |

|---|---|---|

| M=12,ef_construction=60 | 0.87 | 234 |

| M=16,ef_construction=40 | 1.02 | 234 |

| M=24,ef_construction=40 | 1.45 | 234 |

pg_embedding_hnsw (hnsw)

| Parameters | Build time (min) | Index size (MB) |

|---|---|---|

| M=12,ef_construction=60 | 1.28 | 234 |

| M=16,ef_construction=40 | 1.16 | 234 |

| M=24,ef_construction=40 | 1.16 | 234 |

Analysis:

- This is the case-in-point why you must measure both performance and recall. From a pure performance standpoint, pgvector’s

ivfflatindex does have higher QPS (though not by much compared to pgvector’shnsw), but at a great expense with recall. - This is a small dataset, so we can’t draw too many conclusions. However, the results show that pgvector’s

hnswimplementation does have very strong performance / recall characteristics on this smaller data set.

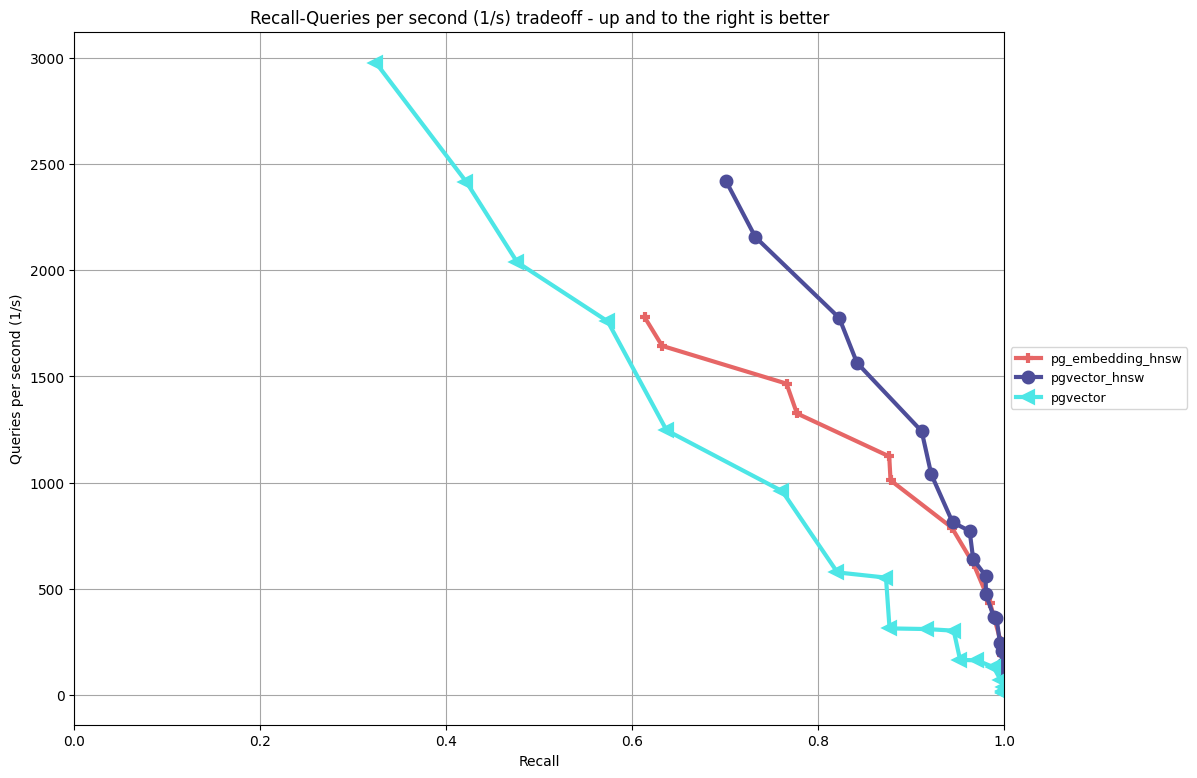

sift-128-euclidean (1M, 128-dim)

This is another data set I like to run against earlier on in my testing, as it’s much larger (1 million vectors) but has lower dimensionality, so testing is generally faster. You’ll also start to see the effect of indexing these vectors at scale. Additionally, because this is lower dimensionality (I still find it amusing that 128 dimensions is “low”), you will see less of the higher dimensionality quirks in your searches.

pgvector (ivfflat)

| Parameters | Build time (min) |

|---|---|

| lists=100 | 0.61 |

| lists=200 | 0.61 |

| lists=400 | 0.63 |

| lists=1000 | 0.75 |

| lists=2000 | 1.35 |

| lists=4000 | 3.58 |

NOTE: I did not get the index size as I did not run the test with this patch in place. However, the index size is roughly the same size as the vector column indexed in the table, plus overhead with the lists

pgvector_hnsw (hnsw)

| Parameters | Build time (min) | Index size (MB) |

|---|---|---|

| M=12,ef_construction=60 | 12.20 | 769 |

| M=16,ef_construction=40 | 15.91 | 782 |

| M=24,ef_construction=40 | 25.23 | 902 |

pg_embedding_hnsw (hnsw)

| Parameters | Build time (min) | Index size (MB) |

|---|---|---|

| M=12,ef_construction=60 | 14.08 | 651 |

| M=16,ef_construction=40 | 11.27 | 651 |

| M=24,ef_construction=40 | 11.88 | 710 |

Analysis:

- Again, it’s crucial to look at both performance and recall.

ivfflathas high throughput, but on this test, it underperforms bothhnswimplementations when looking at the same relative recall. - pgvector’s

hnswimplementation achieves better performance and recall compared to the other two algorithms on this data set, though they all trend towards similar performance when increasing the search area. ivfflatis incredibly quick for building indexes (and note this leverages the parallel build feature in v0.5.0).- We can start to see some differences in index build time and size between the two HNSW implementations. On the surface, it appears increasing

ef_constructionimpacts pg_embedding’s HNSW implementation, whereas for pgvector it’s in increasingM, but this would require a deeper investigation on varying the parameters to draw additional conclusions.

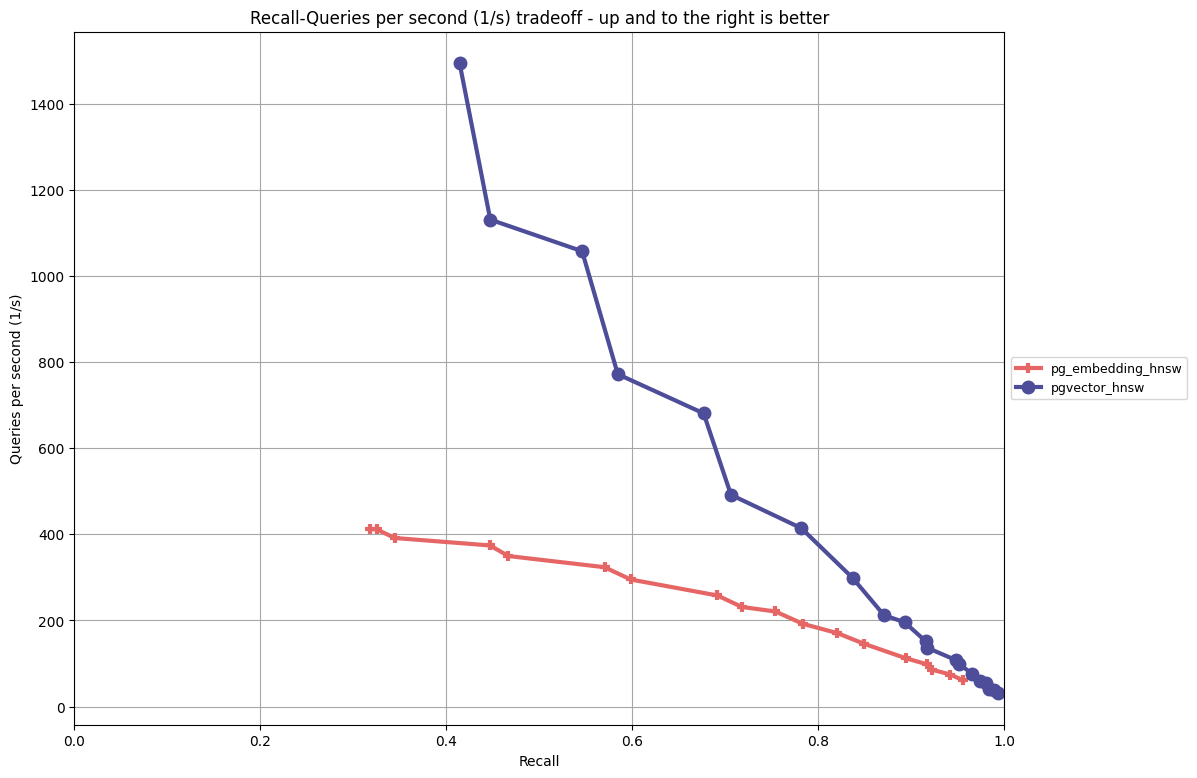

gist-960-euclidean (1M, 960-dim)

I like this dataset because this is where you start to see different implementations sweat. It has a nice size (1M vectors) and a higher dimensionality (960), so your index building and lookups are going to need to do more work.

I did not include the ivfflat implementation in this test due to time so I could prioritize the final test.

pgvector_hnsw (hnsw)

| Parameters | Build time (min) | Index size (MB) |

|---|---|---|

| M=12,ef_construction=60 | 41.37 | 4,316 |

| M=16,ef_construction=40 | 60.20 | 7,688 |

| M=24,ef_construction=40 | 112.04 | 7,812 |

pg_embedding_hnsw (hnsw)

| Parameters | Build time (min) | Index size (MB) |

|---|---|---|

| M=12,ef_construction=60 | 50.48 | 3,906 |

| M=16,ef_construction=40 | 45.77 | 3,906 |

| M=24,ef_construction=40 | 49.01 | 3,906 |

Analysis:

- From both a performance/recall standpoint, pgvector’s HNSW implementation outperforms pg_embedding on this data set, though the gap closes for higher values of

ef_search. - pg_embedding has smaller indexes on this build, and pgvector’s index build time increased with larger values of

Mwhereas pg_embedding stayed flat. There’s likely wor

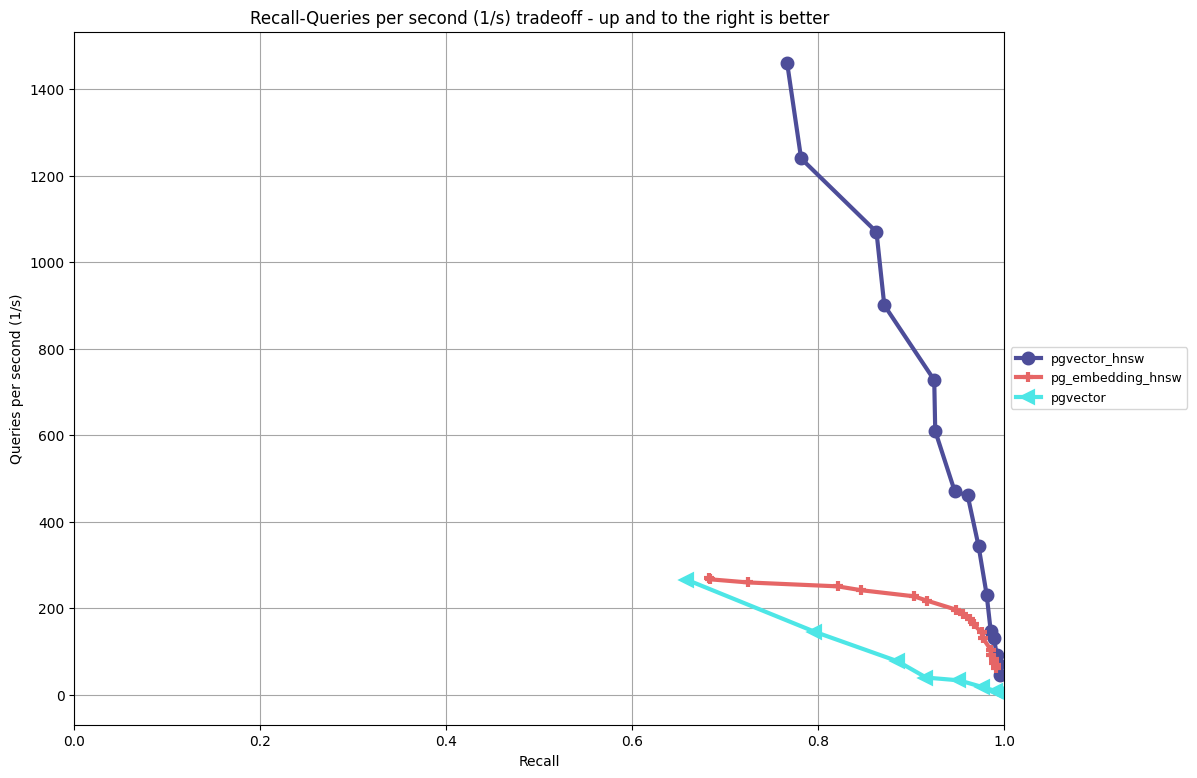

dbpedia-openai-1000k-angular (1M, 1536-dim)

This is the dataset-du-jour that provides vector data that is similar to what you would find in an LLM, in this case, 1536 dimensional vectors. Unlike the other examples above, this data set uses a cosine distance operation.

pgvector (ivfflat)

I only completed two runs, and would like to re-run it again during the next point-in-time evaluation of the algorithms.

| Parameters | Build time (min) |

|---|---|

| lists=200 | 16.55 |

| lists=400 | 16.68 |

NOTE: I did not get the index size as I did not run the test with this patch in place. However, the index size is roughly the same size as the vector column indexed in the table, plus overhead with the lists

pgvector_hnsw (hnsw)

| Parameters | Build time (min) | Index size (MB) |

|---|---|---|

| M=12,ef_construction=60 | 49.40 | 7,734 |

| M=16,ef_construction=40 | 60.10 | 7,734 |

| M=24,ef_construction=40 | 82.35 | 7,734 |

pg_embedding_hnsw (hnsw)

| Parameters | Build time (min) | Index size (MB) |

|---|---|---|

| M=12,ef_construction=60 | 72.22 | 7,734 |

| M=16,ef_construction=40 | 67.06 | 7,734 |

| M=24,ef_construction=40 | 68.56 | 7,734 |

Analysis:

- pgvector’s HNSW implementation has better performance/recall ratio than the other algorithms by a fairly wide margin.

- You can’t beat ivfflat in index building times: you can understand why it’s popular as a coarse quantizer. The index building times between pgvector’s HNSW and pg_embedding’s HNSW are more comparable here, which may be due to the implementation of the cosine distance functions.

- I’m surprised the indexes are the same size; I need to drill into that more.

What’s next?

As mentioned, this is just a first look at pgvector’s HNSW implementation at a specific commit (600ca5a7). Even since I ran the tests, there have been additional commits that iterate on its HNSW implementation. I’m personally excited to see where things land for the v0.5.0.

This is also to serve as a lesson that this is a fast moving space, not just for storing vector data in PostgreSQL, but in general. As I mentioned in Vectors are the new JSON in PostgreSQL, while the vector itself is very old, modern processing research is still relatively new (~20 years) and we’re still finding new innovations in this space. There are still some proven research techniques that pgvector can adopt that will help in all areas: performance/recall, index sizes, and build times.

I think PostgreSQL will continue to be in a place where folks want to use it as a vector database, not just because it’s convenient, but because it can handle the demands of high performance workloads. The addition of the HNSW algorithm to the PostgreSQL extension ecosystem is one step, though a big step, in continuing to help people successfully store and search over vector data in PostgreSQL.